No. 7 | May 1, 2019

Eastside Stories

Eastsiders Pay the Toll

Eastside Stories is our way of sharing Eastside history through the many events, people places and interesting bits of information that we collect at the Eastside Heritage Center. We hope you enjoy these stories and share them with friends and family.

When tolls made their reappearance on the Evergreen Point floating bridge in 2011, many commuters traveling to and from the Eastside were not happy. But this was really a return to the historic norm: for most of Eastside history, it has cost something to take a car across Lake Washington.

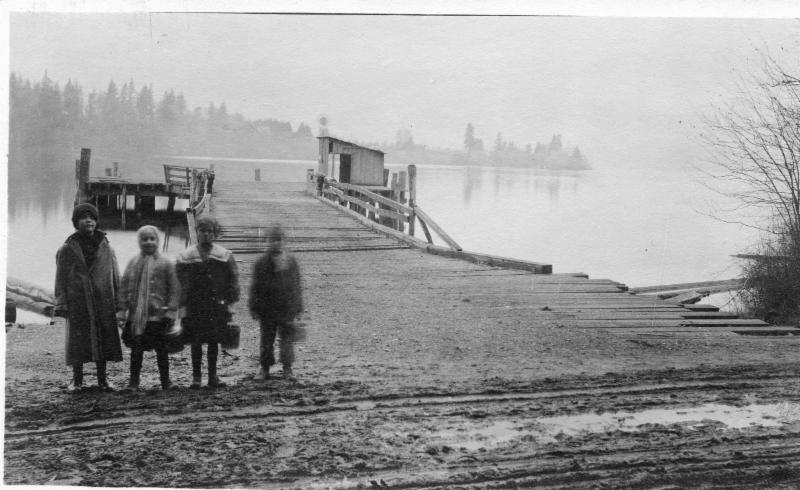

All the early passenger steamers charged a fare, of course, and with the introduction of car ferries to Kirkland, and then to Bellevue and Medina, cars could cross the lake at a price. A ferry schedule for both routes from 1930 shows a fare of 50 cents one way and 75 cents round-trip for “light cars” and 60 cents one way and 90 cents round-trip for “heavy cars,” the cut-off point between light and heavy being 2,600 pounds.

The Seattle-Medina ferry came to an end in 1940 when the new floating bridge opened between Mercer Island and Seattle. And as with most major bridge projects funded by state bond issues, it came with tolls. The toll plaza was located at the first turn onto Mercer Island from the floating bridge, and the toll was set at 25 cents for the car and driver, and another five cents for each passenger. The state removed the tolls when the bonds were retired in 1949.

The new bridge offered a much faster trip across the lake, and one at half the fare. The loss of the ferry turned Medina into a bit of a backwater, and the the new bridge raised the profile of the sleepy village of Bellevue.

A cheerful toll collector greets a driver heading across Mercer Island to Seattle in 1940.

By the mid-1950s, when the massive developments at Lake Hills, Eastgate and Newport Hills began to lure families “over the bridge and to a new way of living,” there were no tolls on the Mercer Island bridge and the commute to Seattle was an easy one.

By the late 1940s, as the Mercer Island bridge was filling up faster than planned, thoughts of a new bridge began to bubble up among Eastside leaders. Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, Congress was hashing out the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act that provided 90 percent of the funding for a national network of freeways.

States could keep tolls on existing bridges and turnpikes that were incorporated into the new Interstate network, but newly built Interstate freeways were supposed to be toll-free: Interstate 90 across Mercer Island would never have tolls, even on the new and very expensive bridge that opened in 1989.

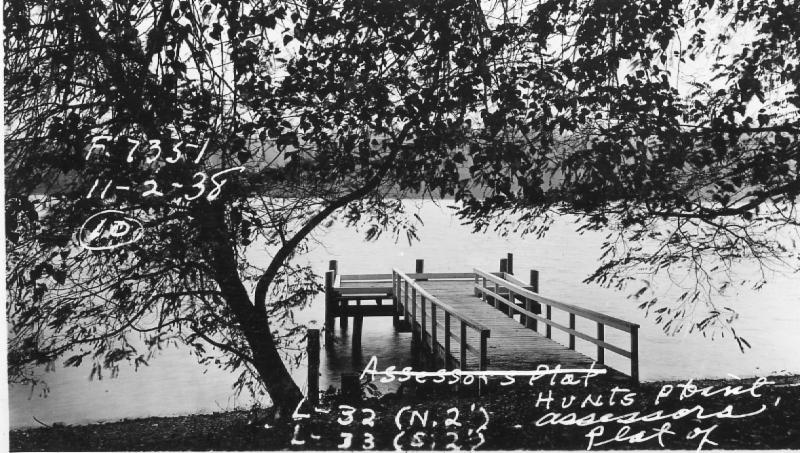

Toll plaza on Mercer Island, looking across Lake Washington to Seattle

The same could not be said for the new SR-520 corridor planned from Seattle to Redmond. It would not be part of the Interstate system and would need to be funded in-state. So, once again, tolls entered the picture. The new Evergreen Point Bridge, opened in 1963, had a toll plaza in Medina and collected 35 cents per car, with no extra toll for passengers. Commuters could purchase books of tickets that cost about 19 cents each. To encourage ridesharing during the energy crisis of the 1970s, tolls were reduced to 10 cents for cars with two or more passengers.

Toll plaza for the Evergreen Point bridge in Medina

The ticket books led to one of the more curious criminal enterprises in Eastside history. In the early 1970s, a group of toll collectors began to purchase those 19 cent tickets and swap them for the 35 cent cash tolls they collected, which then went into their pockets. Over time, these 16 cent “profits” added up to many thousands of dollars. The perpetrators were eventually caught and a number of well-known faces in the tollbooths disappeared.

As with the bridge over Mercer Island, traffic volumes on SR-520 exceeded expectations and the state retired the construction bond early. Tolls came off the bridge in June of 1979.

It took some significant changes in state law to return tolls to the original SR-520 bridge in order to fund the new bridge that had not been built yet. And we can safely assume that those tolls will remain in place long after construction bonds for the new bridge are paid off.

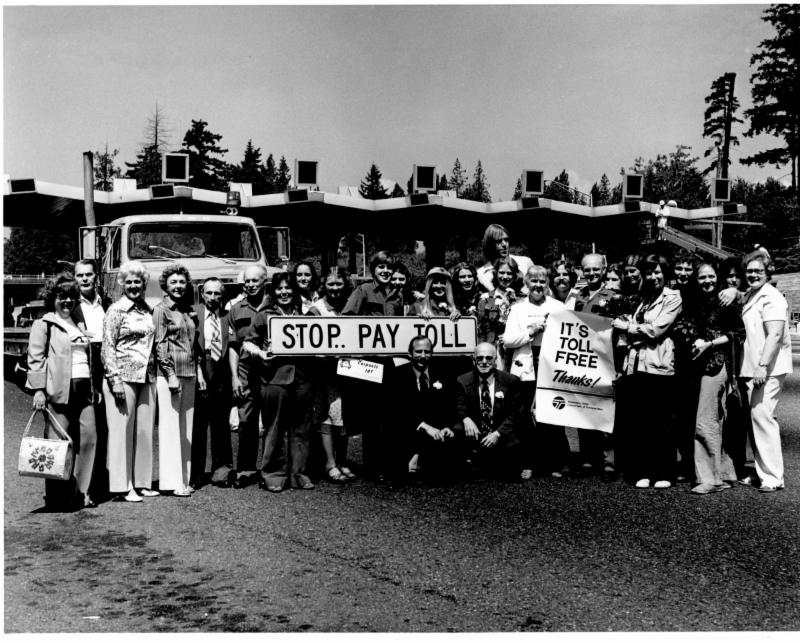

Dignitaries celebrate the end of tolls on the SR-520 bridge in 1979. 32 years later, tolls would reappear, but without a toll plaza or toll collectors.

Economists love tolls, as do government officials charged with paying for really expensive infrastructure. The popular (too popular?) Express Toll Lanes on Interstate 405 would seem to signal that the Eastside will see more, rather than fewer, tolls in the future.

Note on photos. All images in this article are the property of the Washington State Department of Transportation and are in the public domain. These images have appeared in EHC books. The Eastside Heritage Center has a vast collection of images that it owns, but also uses images from public domain sources to help tell its stories.

If you would like to display historic images in your home or business or use them in publications or presentations, please contact us at collections@eastsideheritagecenter.org

Learn more about the Eastside. Books available from Eastside Heritage Center include:

Lake Washington: The Eastside

Bellevue: the Post World War II Years

Our Town, Redmond

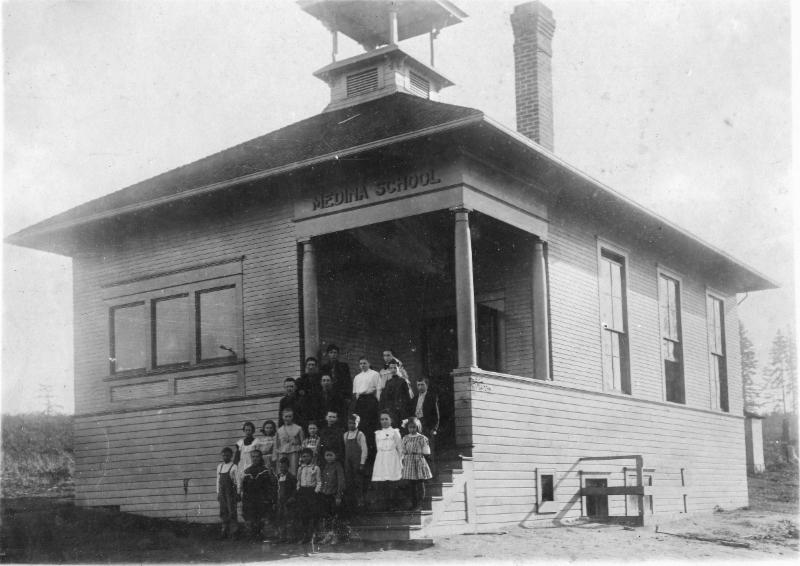

Medina

Hunts Point

Bellevue: Its First 100 Years

Our Mission To steward Eastside history by actively collecting, preserving, and interpreting documents and artifacts, and by promoting public involvement in and appreciation of this heritage through educational programming and community outreach.

Our Vision To be the leading organization that enhances community identity through the preservation and stewardship of the Eastside’s history.

Eastside Heritage Center is supported by 4 Culture