BY Barb williams, EASTSIDE HERITAGE CENTER VOLUNTEER

Early Japanese pioneers in Bellevue often lived in abandoned Indian dwellings. They mostly worked on the railroads, in the sawmills and clearing lands for agriculture. They cleared Clyde Hill, Wilburton Hill, Hunts Point and Yarrow Point to name a few. Cutting the trees and dynamiting the huge stumps was a dangerous and a slow process. The area was covered with dense forests of old growth trees sometimes five feet in diameter. It could take a week to process one tree.

Two early Japanese pioneers to Bellevue were Mr. Jusaburo Fujii and Mr. Kiichi Setsuda who arrived in 1898. The latter worked as a houseboy at Mr. Hunt’s place on Hunt’s Point where he grew potatoes. The former worked at local sawmills and as a cook for Mr. Dagwood who owned an Alaskan cannery. When not working at the cannery, Mr. Fujii worked as the ‘field boss’ for the gardens where Mr. Dagwood grew strawberries. As ‘field boss’ Mr. Fujii hired Japanese workers. Thus began the colorful story of the strawberry. The success of this plant as a highly desirable and productive crop in Bellevue was largely due to the hard work, experiments and skilled agricultural practices of Japanese farmers. At first they leased land for the required minimum of five years; the average life of a strawberry field. With this relatively stable commitment, they began to bring their wives and other family members to the area from Japan. Having made enough money, some were able to buy lands from the railroads.

J98.10.01.a-d - Strawberry pickers on the Takeshita farm in Bellevue, 1933

In 1904, the Wilburton trestle was built by the Northern Pacific Railroad bringing transportation and land opportunities to the Bellevue Midlakes area. Several Issei (Japanese-born) families bought land to farm. They set up successful farms growing pole beans, peas, tomatoes, strawberries, cabbages, cucumbers, celery and lettuce. In 1919, with the help of a Japanese-American attorney, the Takeshita family bought 13 acres just east of the railroad tracks and north of Lake Bellevue. Several other families bought adjacent property which they turned into productive agricultural lands located primarily in the Midlakes area. Wilburton and downtown Bellevue became Japanese farmlands as well. Between 1905 to 1938, there were 32 Issei who owned land: some of whom were Takeo (Tom) Matsuoka, Asaichi Tsushima, Itaro Ito and Takayushi Suguro.

Strawberry production was very successful and the fruit so popular that in 1925 a group, including Japanese farmers, got together to initiate the first Bellevue Strawberry Festival, complete with a Queen. The highlight of the festival was the scrumptious strawberry shortcakes with sun-ripened red strawberries topped with thick cream from local dairies. The majority of the strawberries were grown and provided by Bellevue Japanese farmers. The annual festival continued until 1942.

1994BHS.024.001 - 1939 view of Japanese farms near Midlakes

Despite the enactment of the Washington State Alien Land Law (March 2, 1921) that denied Japanese the right to purchase land, Issei (born in Japan) who had already purchased land could retain it and Nissei (Japanese citizens born in the United States) could purchase land. Thus the Japanese community and farmers continued to grow and prosper. With the leadership of members of the Bellevue Japanese Community Association, The community Clubhouse (Kokaido) was built in 1930 at 101st Avenue NE and NE 11th Street. It provided a space for language classes, social gatherings, services and active Japanese sports.

By 1931, Japanese-American farmers on the Eastside were shipping produce throughout the northwest via the Northern Pacific Railroad. Peas sold for approximately one cent per pound and strawberries for about one dollar a crate. As produce continued to flow in and out of Bellevue, the Bellevue Growers Association (organized in 1930) recognized the need for a central distribution site. In 1933 they helped build a shipping/packing shed in Midlakes alongside the railroad tracks at 117th NE & NE 10th. Three full-time, year-round employees were hired: a business manager, bookkeeper and floor manager assisted by 20 seasonal workers. Tom Matsuoka, who was very active in the Bellevue Growers Association, became the business manager. His marriage to Kazue Tatsunosuke was the first Bellevue marriage of a Nisei; Kazue being born in the United States.

Prior to World War II, there were about 300 Japanese Americans living in Bellevue comprising 15% of the general population and 90% of the agricultural workforce. It was around this time (December 7, 1941) that Tom Matsuoka remembers the sunny afternoon when he was preparing plants for the winter. Suddenly his daughter, Rae and friends, came running saying, “ There’s a war started. ---- The Japanese planes have bombed Pearl Harbor!” Tom was thoughtfully silent. Then he went back to tending his plants. Shortly thereafter several prominent Japanese community leaders, including Tom, were taken away to incarceration camps; Tom to Montana. Later he joined his family at Tule Lake, California.

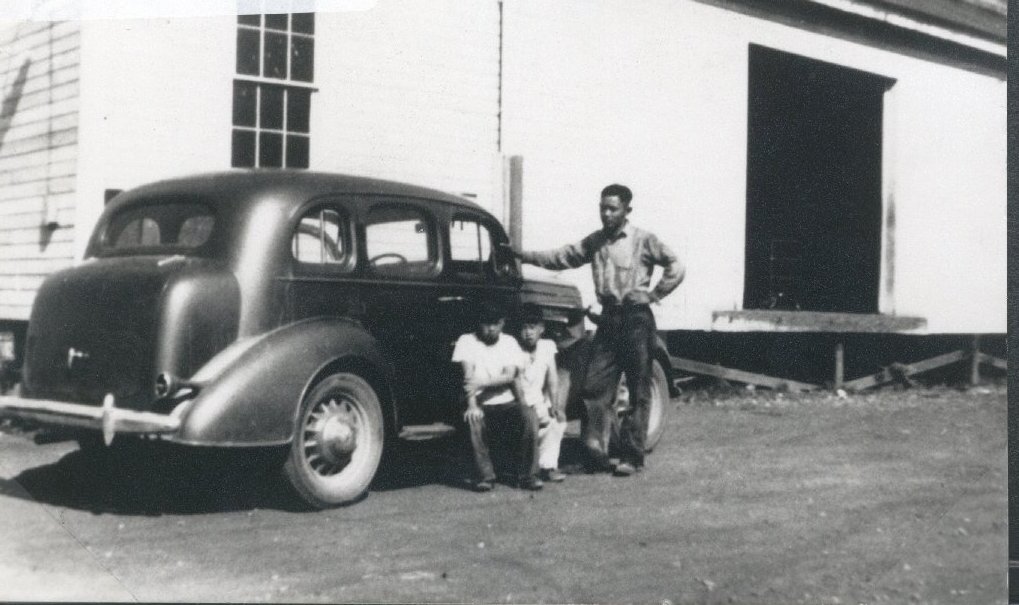

J 89.02.02 - Tom Matsuoka and his sons, Ty and Tats, outside of the Bellevue Vegetable Growers Association shed. 1933

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 ordering all people of Japanese decent to incarceration camps. In May 1942, all Japanese people (Issei and Nisei) in Bellevue were taken from their homes and sent to the Pinedale Assembly site near Fresno, California. The fields with strawberries ready to be harvested were empty of Japanese pickers and the Strawberry Festival was cancelled.

Sumie Akizuki, Nisei daughter of Issei Bellevue residents Takayoshi and Michi Suguro, remembers those tough times as she writes:

“We took the train at a station in Kirkland, and what an irony it was that we would go right pass our farm which was located right next to the railroad tracks. We could see the neat rows of the strawberry fields and our house in the distance. As the train went by, my parents saw their farm for the last time, focusing their eyes on the farm until it disappeared into the horizon. I’m sure it was heartbreaking to lose all they had worked so hard for. Going to camp was the first time I had been on a train. When I was growing up, I wished that someday, I could ride a train on the Wilburton Railroad Trestle. I would look up in awe at the trestle, which impressed me so much during my childhood. ——-. It is an irony that my dream came true when I rode on the trestle, on a coal driven locomotive, that took me to the Pinedale, California assembly center. What seemed like an adventure was not at all like I thought it would be, since it was a time of sadness and uncertainly.”

Fifty years later, she rode the dinner train across the trestle with family and friends.

In 1993 four Japanese cherry trees were planted in the Bellevue Downtown park to honor the Japanese immigrants and their contributions to the growth of Bellevue. A plaque reads: “To honor the Bellevue citizens of Japanese ancestry who had so enriched our community”.

Sources:

Eastside Heritage Center archives

Sumie Akizuki letter

Journal American newspaper article, “The Clearing of Bellevue”, May 10, 1992.

Asaichi Tsushima, document “Pre-WWII History of Japanese Pioneers in the Clearing and Development of Land in Bellevue, 1952,

Rose Yabuki Matshushita, 1997 - Excerpt from presentation on Executive Order 9066 at Marymoor Museum

North American Post, article “ part 3 of an 8-part series: Bellevue’s Nikkei Roots”. 12/12/1997.

Publication of the Seattle Times: A Hidden Past. c. 2000

photo: 1936 showing 7 Japanese farms along 117th NE & NE 11th, photo courtesy of Mitsuko (Takeshita) Hashiguchi

Book: Bellevue Timeline by Alan J. Stein & The HistoryLink Staff, c.2004