By Shannon Advincula, Eastside Heritage Center Intern

The Japanese characters written on the back of these wooden slatted folding chairs indicate that they had been used at the “Bellevue Japanese People’s Clubhouse (ベルビュウ日[本]人会).” Kokaido, the Bellevue Japanese Community Clubhouse (or Community Hall), had been established at 101st Avenue NE and NE 11th Street in 1932, and served as a hub for the Japanese American community on the Eastside.[1]

2008.014.001

Kokaido Chairs, donated to the Eastside Heritage Center by Sumie Akizuki.

Kokaido hosted a plethora of community activities, such as business meetings, Buddhist and Christian church services, flower arranging classes, movies, Japanese language classes, shibais (plays), various sports, and picnics. An article published in the Japanese-American Courier in 1933 describes how the Japanese American community in Bellevue used the space almost daily: “On Saturdays it housed the Japanese Language School. On Sundays it housed church groups. And the rest of the days of the week are filled with activities such as judo, basketball and meetings of all organizations. Occasionally parties and movies are held."[2]

Image: L 89.029.002.

Photograph of the dedication of Kokaido, the Bellevue Japanese Community Clubhouse. Community members stand in front of the clubhouse building which had stood at 101st Avenue NE and NE 11th Street.

Prior to World War II, the Japanese American population in Bellevue numbered over 60 families and over 300 people, comprising 15% of the general population and 90% of the agricultural workforce.[3] The Bellevue Japanese American community pooled together donations to purchase two acres in what is now downtown Bellevue and built Kokaido in 1930.[4] The dedication gathering in 1932 was attended by an estimated 500 people, including Bellevue's leading citizens. Later, in 1937, a second building was added, providing more room for community space and a worship center.

J 89.04.03

Women's basketball team, c. 1930’s. Photograph taken at the Japanese Community Clubhouse in Bellevue.

At the time of the clubhouse’s construction, Tom Matsuoka and the Seinenkai, a club of Japanese American youths comprised of Bellevue Nisei (second-generation Americans of Japanese ancestry born in the U.S.), advocated for the building to be built 60 feet high in order to accommodate indoor basketball activities.[5] Both men and women participated in indoor and outdoor sports and recreational activities that centered around Kokaido, forming Japanese American Bellevue teams and participating in regional tournaments for various sports including basketball, baseball, and the Japanese martial arts of judo and kendo.

By January 1932, the Bellevue Dojo which hosted judo activities had about thirty-five members, which was about half of the total membership of the Bellevue Seinenkai. The judo club even organized its own events, including taffy pulls, roller skating and Halloween parties, Japanese movie nights, picnics, and demonstrations at the local high school and Bellevue’s annual strawberry festival.[6] The venue for many of these activities and tournaments was the Japanese Community Hall in Bellevue.

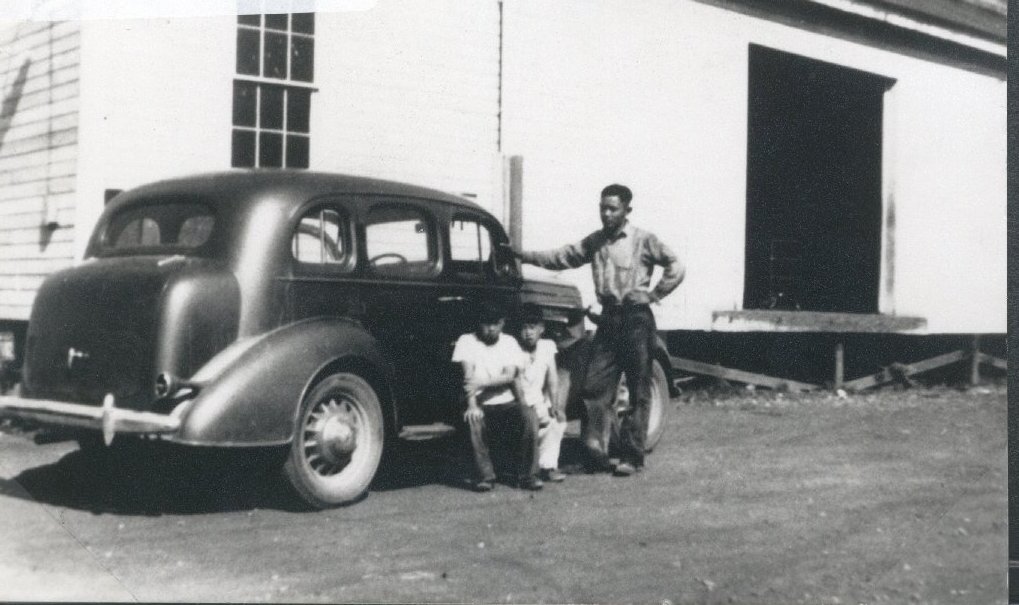

J 89.04.01

Photograph of the championship Bellevue baseball team at an annual three day tournament for the Puget Sound Area Japanese teams, held in Seattle c. 1930’s. Tokio Hirotaka was the team coach, and is standing on the right in the back row.

But the bustling daily life of Japanese Americans would ultimately be suddenly disrupted and irrevocably altered. On the evening of December 7, 1941, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI started arresting Japanese American community leaders in Bellevue: the schoolmaster of the Japanese language school, the head of the Japanese businessmen’s association, and Tom Matsuoka, who was president of the Bellevue Vegetable Growers Association. The Seattle Times wrote in a 1997 investigative article that, “[Their] arrest was one of many mistakes the FBI made in those sweeps… It was clear that the three were targeted mainly to decapitate, as it were, the Nikkei community, not because of any actual threat they might pose.”[7]

443 Eastside men, women and children, including 300 of them from Bellevue, were forced into incarceration camps until the end of the war. They were forced to vacate their personal properties, and Kokaido was left abandoned without its community. After the war, many Japanese American families did not return to Bellevue, and the approximately 20 families of the original 70 that did had a difficult time rebuilding their land, businesses, and community.[8]

In 1950, the clubhouse building was sold by the Bellevue Nisei Club, Inc. to the Board of Missions of the Augustana Lutheran Church for $11,000. Pastor Olson of the Lutheran congregation recorded that, “the Japanese-American group had others who wanted to purchase the property, but declined all the offers because they were from businessmen who wanted it for commercial purposes. They were happy to know this sacred property would be used for a church.” Through the purchase agreement, a Japanese American community member named H. Kizu was also provided living quarters at the church and employed. Ultimately, the building was sold again in 1964, and eventually demolished.[9]

Asaichi Tsushima, in his memoir Pre-WWII History of Japanese Pioneers in the Clearing and Development of Land in Bellevue, wrote of the closure of Kokaido, saying, “One of the changes at the end of WWII that saddened and disappointed me was the sale of the Japanese Community Clubhouse and property where so much of our lives had been centered.”[10]

J 89.07.01

Photo of "Dedication: A Play,” possibly from the Kokiado. Copied from Asaichi Tsushima, "Pre World War II HIstory of Japanese Pioneers in the Clearing and Development of Land in Bellevue," 1939.

The economic, social, and cultural life of the Japanese American community in Bellevue was sustained and enriched in part by everyday community and recreational activities such as those hosted by Kokaido. These chairs and photographs are a reminder of the large and vibrant Japanese community of farmers, businessmen, and families that helped to establish and shape Bellevue; a community which almost disappeared and was never the same after WWII incarceration.

Footnotes:

[1] Asaichi Tsushima, Pre-WWII History of Japanese Pioneers in the Clearing and Development of Land in Bellevue (1952).

[2] Japanese-American Courier, 1 Jan 1933.

[3] Publication of the Seattle Times: A Hidden Past. c. 2000

[4] Bomgren, Marilyn, “The Bellevue Japanese American Clubhouse: My Story of Life in the Bellevue Japanese American Clubhouse,” 2008.

[5] Matsuoka, Tom. “Tom Matsuoka Interview.” Courtesy of Densho, 1998. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-47-16/?tableft=segments

[6] Svinth, Joseph R., Letter to the Marymoor Museum, 1998.

[7] Keiko Morris, Seattle Times Eastside bureau 8/20/97

[8] The Seattle Times, “A Hidden Past: An Exploration of Eastside History”. 12/1997 - 1/2000.

[9] Bomgren, “The Bellevue Japanese American Clubhouse,” 2008.

[10] Asaichi Tsushima, Pre-WWII History of Japanese Pioneers in the Clearing and Development of Land in Bellevue (1952).