Eastside Stories is our way of sharing Eastside history through the many events, people places and interesting bits of information that we collect at the Eastside Heritage Center. We hope you enjoy these stories and share them with friends and family.

Article by: Tom Hitzroth

Frontier towns were typically constructed of wood and could be partially or totally destroyed by a fire that started from a chance spark from many different sources. No community large or small was safe from fire and Redmond was no exception.

On October 26, 1889, William E. Sikes purchased a lot from Luke McRedmond and built the first hotel in Redmond. Sikes called it the Valley Hotel. At this time Redmond was still transitioning from the settlement period in its development and it would be another decade before it took on the character of a town.

Sometime in 1904 or early 1905, Herman S. Reed purchased the property from William Sikes and in 1906 Mary Walther began remodeling the Valley Hotel. The new hotel opened for business as the Hotel Walther by May 1, 1907. On May 12, 1908 Mary Walther purchased the property from Herman S. Reed. On March 13, 1910, a fire started in the hotel. The following is a likely progression of the event based on analysis by a senior fire investigator for the Redmond Fire Department of photographs taken on that day by Winfred Wallace together with the reports from the four major Seattle newspapers.

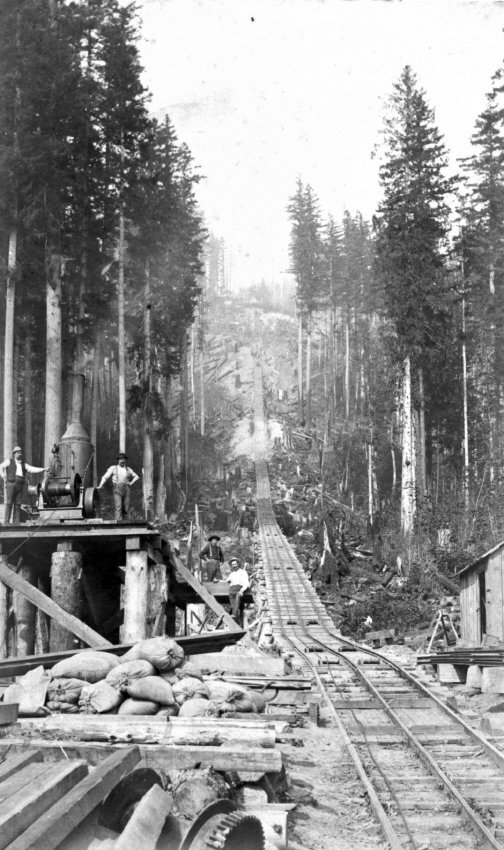

The investigator verified the chimney was the source of the fire, and explained how the fire spread on the third floor. The first photograph below shows the fire’s progression approximately 15 to 20 minutes after it began. The burn pattern on the east end of the third floor (right in the photograph), and destruction to the window frame suggested that the fire reached an intensity that exploded the third floor window. He also determined, from the way the rafters are exposed the north side of the third floor (farthest away in the photograph) burned faster than the south side.

Once the fire had begun a bucket brigade was formed to save the adjoining property. A call for help was put out to the neighboring communities and Kirkland answered the call. The Kirkland firefighters dragged two pieces of equipment four miles to the scene. However, since Redmond was not on a water system the equipment could not be employed effectively. Unable to suppress the fire there were only a couple of alternatives left. They could let the fire burn, contain it the best they could, and hope it didn’t spread to the rest of the town, or they could try a controlled demolition to bring the fire to an end. It was decided to try a controlled demolition.

The building on the right in the second photograph, though damaged by the fire, was brought down by the controlled demolition. The investigator and I discussed the probable placement of dynamite charges that brought the hotel down. Most likely, because the building was 25 feet north of Cleveland Street, Cleveland Street was 60 feet wide, and based on the density of the surrounding buildings, collapsing the hotel toward Cleveland Street would have been the most viable and sensible option. The fire did not completely burn out until the early morning of March 14.

The destruction of the Hotel Walther in 1910 was a major calamity for Redmond particularly as it jeopardized the survival of the town. Through the skill of those unknown individuals who positioned the dynamite charges that helped contain the fire, the only other buildings lost were a small shed and a barn. The upside was that no customer lost personal belongings in the fire, the hotel furnishings were saved, and no one was injured.

Later in 1910 Mrs. Walther rebuilt the Hotel Walther on the northeast corner of Leary Way and Cleveland Street. In 1912 the property was purchased by Harry Evers and renamed it the Grand Central Hotel.

Both photos top and bottom: Walther Hotel burning March 1910. Photographs by Wallace Studio.

Our Mission To steward Eastside history by actively collecting, preserving, and interpreting documents and artifacts, and by promoting public involvement in and appreciation of this heritage through educational programming and community outreach.

Our Vision To be the leading organization that enhances community identity through the preservation and stewardship of the Eastside’s history.